On the left is an early and rare Spanish daguerreotype dating from 1845. Walter Benjamin felt that whereas most mechanical reproductions destroyed the aura of a work of art, such early photographic portraits did have an aura derived from the life of their sitters. Benjamin seemed to grant these portraits an aura because they were used to remember the absent, but I have never understood why a reproduction of a Manet does not then have an aura derived from the original painting, which after all the reproduction is used to remember or stand in for. On the right is a portrait of a young woman by Emile Joachim Constant Puyo, c. 1900. I find it surprisingly non-objectifying, which is to say that the woman feels like a real personality rather than merely an object to be looked at (although inescapably she is that too). Like the daguerreotype this image invites the viewer to go beyond external appearance and wonder who this woman is.

On the left is a “Surimpression” from 1931 by Maurice Tabard and on the right is Irving Penn’s portrait of Sophia Loren and her mother from 1962. Both photos juxtapose two faces, though obviously in different ways. By superimposing the faces on the left, Tabard calls into question their gender and even their humanity. The portrait of the Loren women rather juxtaposes two different ideas of femininity—on the left maternal rectitude, on the right playful sexuality. Yet the biological relationship between the mother and daughter, reinforced by their strong resemblance, encourages us to see these two femininities as coexisting rather than mutually exclusive.

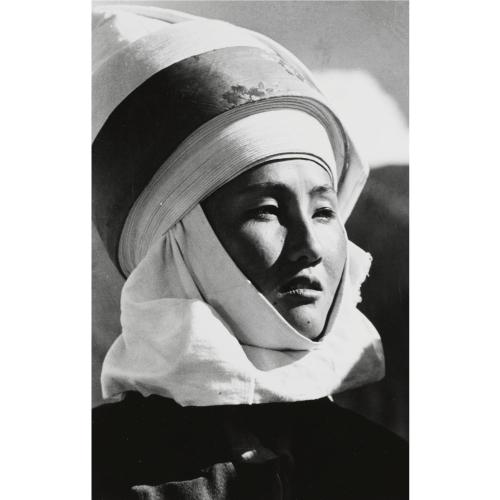

The sale includes many portraits of famous women. On the left is a portrait of Greta Garbo done by Clarence Sinclair Bull in the 1930s. On the right is one of three portraits of British actresses done by Philippe Halsman in the 40s and 50s. I’m guessing it is of Wendy Hiller, when she was starring in a version of “

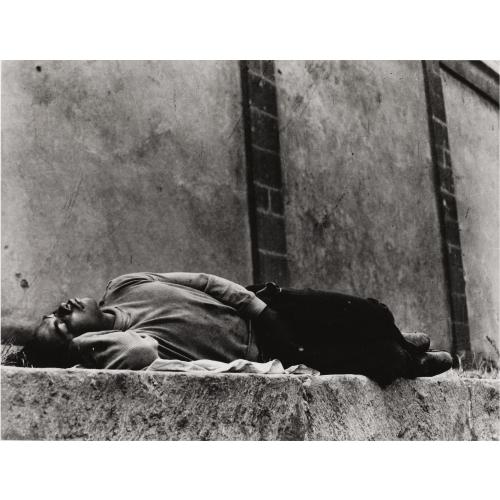

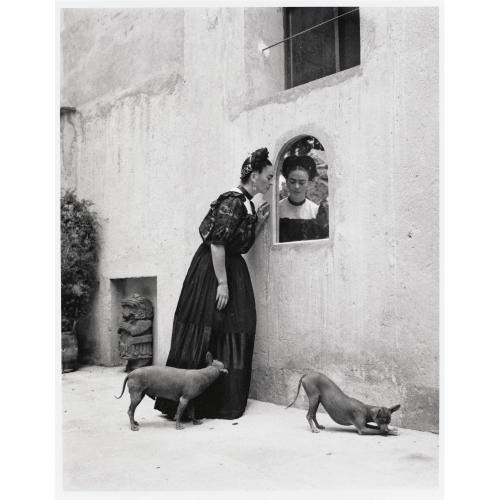

This photograph by Manuel Álvarez Bravo from 1931 is titled Dreamer, and although the woman is lying down, it is the expression on her face which calls that title to mind. The image reminds me of how women have historically been seen as frivolous and self-absorbed, concerned with artifice and imagination. The male equivalent to this image in art is Rodin’s Le Penseur (The Thinker), of an extremely muscular man, a heroic nude in the classical tradition, in extreme concentration. It is perhaps this sense of focused concentration that the Dreamer lacks, and what separates her from the creative and intellectual genius attributed to men. The original title of Rodin’s sculpture was The Poet, because it was meant to depict Dante contemplating the gates of hell, but women have traditionally been denied such artistic identities.

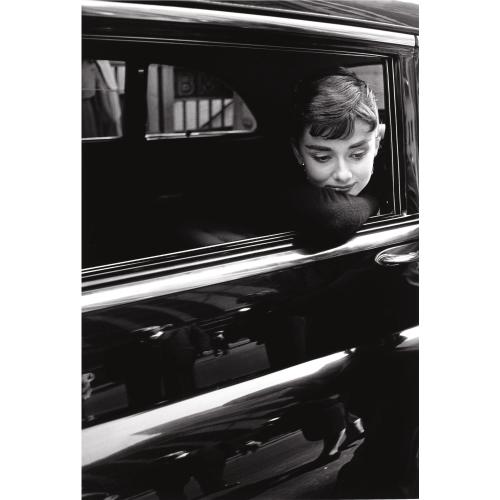

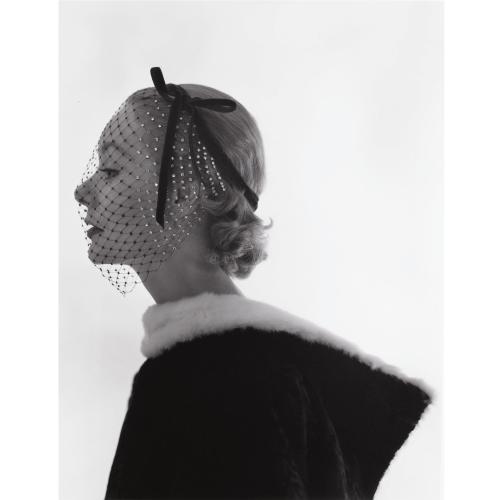

One theme running through depictions of women is the importance of visual boundaries and physical restrictions. Above and to the left, a photo of Audrey Hepburn, shot by Dennis Stock during the filming of Sabrina in 1954, calls to mind Impressionist paintings of women sitting behind balcony railings, theatre boxes, and other representations of cages. Her resigned look downwards further emphasizes her isolation. Whereas the portrait of a

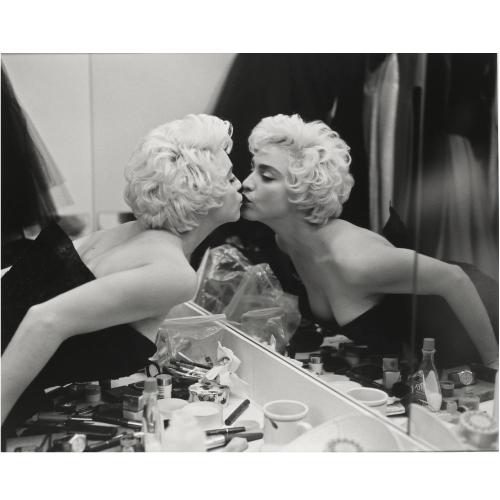

Another longstanding theme or rather attribute in images of women is the mirror, a sign of vanity and sometimes specifically of female vanity. In Bruce Weber’s photograph of Madonna, taken in

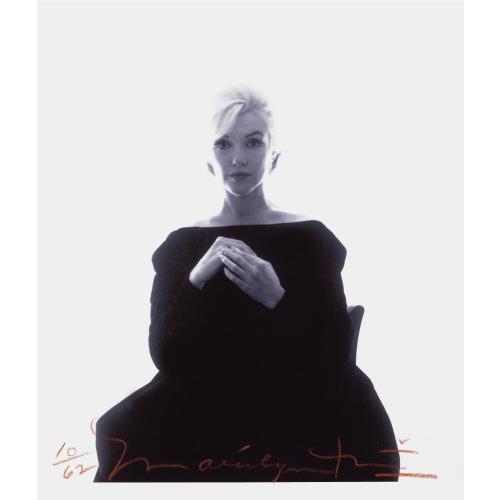

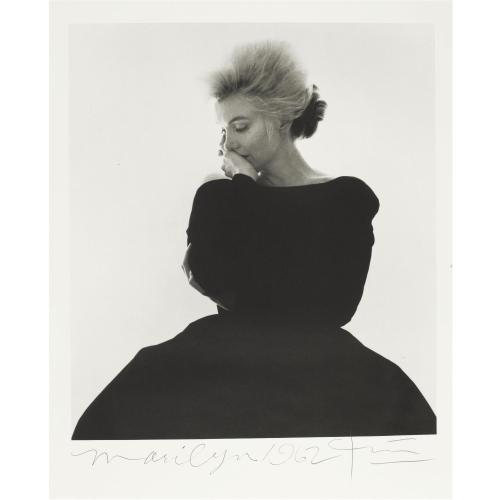

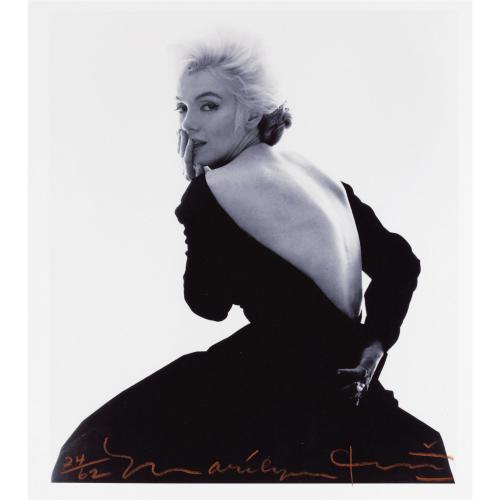

These photographs of Marilyn Monroe show the importance of body language in depicting a mood. They were taken by Bert Stern in 1962 as part of a photo shoot for Vogue magazine. Above, Monroe seems remarkably prim and proper. Her face takes on an angelic beauty quite different from her typically lacquered sexpot image. Yet in the next photo, below left, Monroe has departed even farther from it. Instead of a sleek young pin-up she appears haggard, even old. It is only in the last photo, in which she shows off the low back of the dress, turns most of her body from view and looks back alluringly over her shoulder that she takes on a sexy spin. These images remind me of an anecdote about Monroe, that she was walking down the street with an old friend who was surprised that more people didn't recognize such a famous actress. The former Norma Jean said "you want to see Marilyn Monroe?," stuck out her chest and began to swagger down the sidewalk. So many people recognized her and began asking for her autograph that the police had to be called to break up the riot.

No comments:

Post a Comment